PSA PANIC! An Explainer

Your post-treatment numbers were fine. Then they went up. Your doc's not worried. What gives?

They took my prostate out, and every three months they drew my blood to measure my prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels. And those numbers were great. Undetectable, undetectable, undetectable, undetectable. Six months, then one year, then I was the Cancer-Free Golden Boy. I was back on track. I was moving on. I beat cancer.

But sometime after that, my PSA number doubled. And when I say “doubled,” I mean that it went from 0.01 to 0.021.

I completely spun out, but my doctor said, “Meh, you’re fine.” Yeah, fine for him. He’s not the one that had cancer, I am. I’m the one who’s going to spend the rest of my days monitoring my numbers and looking over my shoulder. And my numbers went up.

I went full panic mode. They’re gonna give me chemo. They’re gonna put the catheter back in. The cancer is back. (Is it?) I have cancer again. (Do I?) They keep saying not to worry. Don’t worry, don’t worry, don’t worry. They’re so confident but I know just one thing:

THE.

NUMBERS.

WENT.

UP.

It turns out the whitecoats were right, but I was never happy with their explanations. I spent a lot of time afraid and worried about my PSA numbers. I could not find anything online or off to explain why I wasn’t supposed to worry. But I figured it out, and I want to share it with you if you’re dealing with this.

Here it is: If your PSA is wobbling around zero-point-zero-something then you should not worry even if it goes up because PSA tests give us TOO MUCH DATA that WE DON’T NEED.

Dude: You do not have cancer again.

Here are four things I can explain without a bunch of jargon that will help you believe this:

How to think about the number the lab gives you.

The fact that “undetectable” is kind of random.

How “signal” and “noise” work in laboratory equipment.

How they actually analyze your blood sample in the lab.

When you put these four things together, you’ll see that the way we measure and act on PSA levels maybe has some problems. The system isn’t broken—in fact, it works too well.

First, let me show you my numbers. Real quick, the symbol “<“ means “less than.” Here’s a nice chart:

1. Thinking about the number the lab gives you

Let’s talk about those letters “ng/ml” just so we’re on the same page here. You may already know this stuff but hang out with me. “ng/ml” means “nanograms per milliliter.”

“milli-” means one thousandth of something, or 1/1000. In the U.S., we buy soda in 2-liter bottles. Pour out half the bottle, then divide the rest of it into one thousand tiny cups. Each cup is a milliliter.

“gram” is used to talk about how much something weighs.1 A paper clip is a gram.

Nano- means a billionth of something. One billionth of a gram. Take that paper clip and cut it into one billion pieces and you’ll have nanograms of a paper clip.

A nanogram is a tiny amount of stuff. Take a moment and think about how small one-billionth of something is. It’s a drop of water in a swimming pool. It’s one second in a 32 year-old man’s life. It’s a stupidly small amount of something.

Saying “nanograms per milliliter” is the same as saying “parts per billion,” or PPB. One part PSA per billion parts of blood. Before you had cancer, you probably had a PSA around 2 PPB. My highest PSA before surgery was 13 PPB.

My first PSA after surgery in January 2023 was LESS THAN 0.01 nanograms, or <0.01 PPB. My PSA in January of 2025 was 0.021 PPB. Okay, that more than doubled. That’s scary, except WAIT A MINUTE GUYS, we’re talking about one percent of a part per billion. One percent of a nanogram per milliliter.

The takeaway here is that PSA is measured very precisely, and by that I mean too precisely. What look like big changes really aren’t. If you take something stupidly small and double it, it’s still stupidly small.

Dude: You don’t have cancer again.

2. “Undetectable” is kind of random

The place where you get your blood drawn is not necessarily the place where your blood gets analyzed. In fact, it’s most likely not. “Laboratory” is where our blood is analyzed. “Needle place” is where we go to get poked.

Each individual laboratory can make its own rules for what the “undetectable” cutoff is. Even labs in the same healthcare system can be (and probably are) different from each other. Labs set the cutoff number, and they can and do change it. Why? There are two answers. First, it might be because some administrator or supervising doctor came in and said, “The cutoff should be this and not this.” The second answer is “I don’t know.” Sorry.

In either case, labs do not tell patients or their doctors when they make these changes.

When you look at my two PSA results for June 2023, you see the number jumped up to <0.14 when it had been <0.01. It looked like in three months my PSA went up ten times higher. That’s a big enough and fast enough change that everyone should be suspicious, and my urologist certainly was. He sent me back right away for another analysis. Same result. Then a month later, it was down to <0.014.

Notice that in all three numbers, the “<“ symbol is still there. When you see “<“ you can assume the number after it is the cutoff number. So it looks like the lab changed the cutoff from 0.01 to 0.14. I was still less than the cutoff, even though somebody changed the cutoff to be ten times higher.

My urologist knew what was happening, because he’d seen it hundreds of times. But he was mighty irritated about it. He said he was going to call the lab system, and I suspect a bunch of doctors called and chewed their asses good.

Oh, and I spent a full month worried about cancer coming back. Or never having left. Good times.

It could be that your blood sample always goes to the same lab. On the other hand, the healthcare system might realize they can save $1.55 per year if they close your lab and deliver samples twice a day to a different city 60 miles away.2 Your PSA result from the new lab will most likely be a bit different. Again, the healthcare system ain’t gonna tell you when they do this.

Look at my last three results:

July 8 2024: <0.014

Jan 6 2025 0.021

Apr 1 2025 0.015

I like July 8. I don’t like January 6 because he “<“ is gone.

“I’m not worried,” said my urologist.

“Why not?” I asked. “Look, it was LESS THAN 0.014 and now it is A SPECIFIC NUMBER which means a specific amount has been DETECTED AND NOW MY PSA IS DETECTABLE.”

“Yes, the symbol is gone,” he said. “But the number is too low to make me worried. If it was 0.1 or 0.2 that’s a concern. This is not a concern to me.”

I pushed back. “But it is not LESS THAN A NUMBER. IT IS NOW A SPECIFIC NUMBER. A specific number has been detected. My PSA is DETECTABLE. SOMETHING IN MY BODY IS MAKING PSA.”

We went around and around like this for about half an hour. We eventually agreed that in three months I would get another reading and if it went up, then we’d go to yellow alert.

And it did not go up. It went down. It went down a tiny bit but it did not go up. There was still no “<“ so I still had questions.

I went to the needle place for answers. “Are you sending PSA samples to a new analytical lab?” I asked

“Yes we are,” they said. “They closed our usual lab and now they get sent to Flint, Michigan. Why do you ask?”

New lab. Maybe they have a different cutoffs. Maybe some decisionmaker said to stop using “<“ because every keystroke costs money. Maybe the instrument was recalibrated. Or they got a new one. Or the old one is getting wibbly. I wanted to get 0.014 and I got 0.015. The difference is 1/1000th of a billionth of a gram of PSA.

Dude: I don’t have cancer again.

One of the other things my urologist said to me was that the variability in my results could very likely be “noise” from the analysis. So let’s talk about that.

3. How “signal” and “noise” work in laboratory equipment that measures our PSA

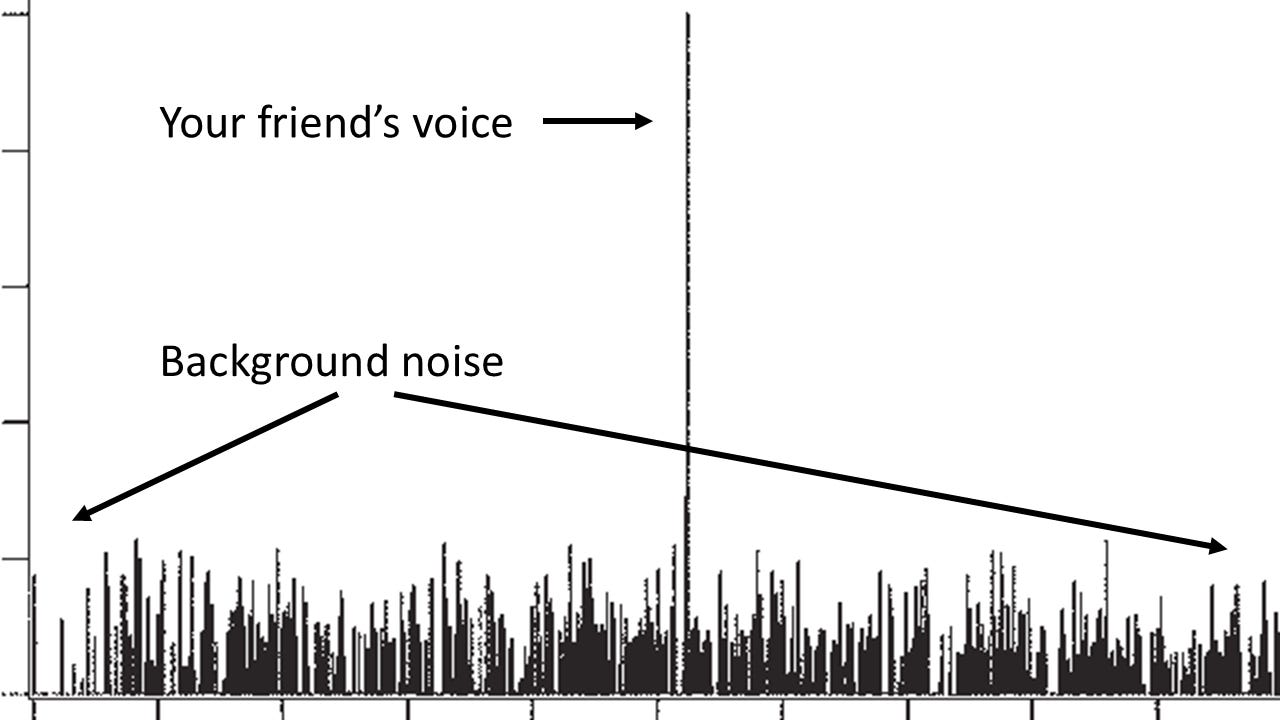

Let’s say you and a friend go out to a restaurant to have a meal and a nice conversation. The restaurant is empty except for the two of you, so it’s easy to hear your friend talking. If you made a picture of your conversation in a quiet restaurant, it might look like this:

The big spike is your friend’s voice coming at you loud and clear, which we’ll call the signal, because that’s what you’re interested in hearing. The little bars and squiggles represent background noise, like the music or dishes clinking. The signal-to-noise ratio is good.

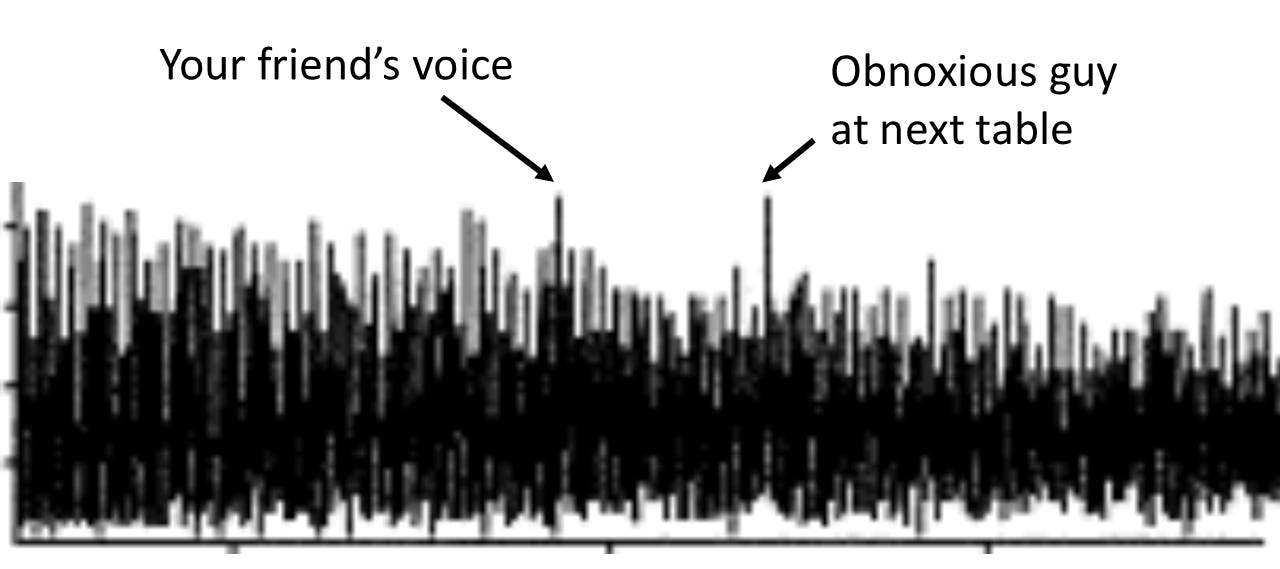

If you go to the restaurant when it’s very busy, you have to strain to hear your friend’s voice, and the background noise is really loud. The picture of your conversation might look like this:

The signal-to-noise ratio here is very bad, and some of it overpowers your signal. Your friend keeps talking louder, but you can’t really hear him over the noise.

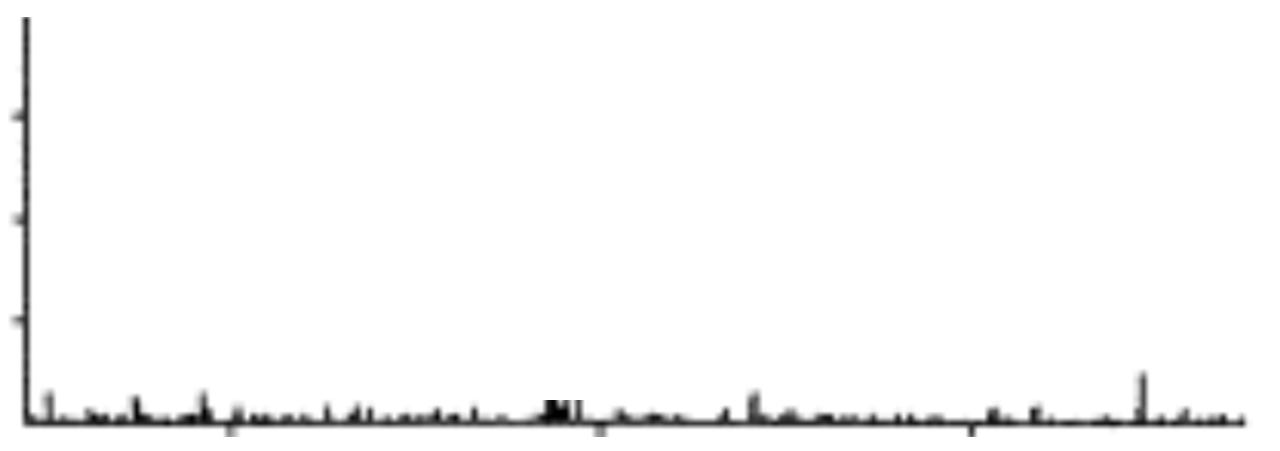

No matter what restaurant you go to there is noise, but a good one will let you at least “detect” your friend’s voice. The same principles apply to the scientific instruments that are used to detect our PSA. No matter how precise your instrument is, there’s always noise. An instrument just sitting there plugged in but not running a sample will have a readout that looks something like this:

The little bars are noise. Technically, it’s reporting PSA when it’s not analyzing a sample. What’s causing this? Lots of things: The electricity powering the instrument, nearby instruments that are plugged in, the wiring in the building, the air conditioning or heating, the humidity, cosmic rays, the Earth’s magnetic field, even a mobile phone sitting nearby.3 This is for real; a sensitive scientific instrument will detect a lot of noise. Noise changes from moment to moment.

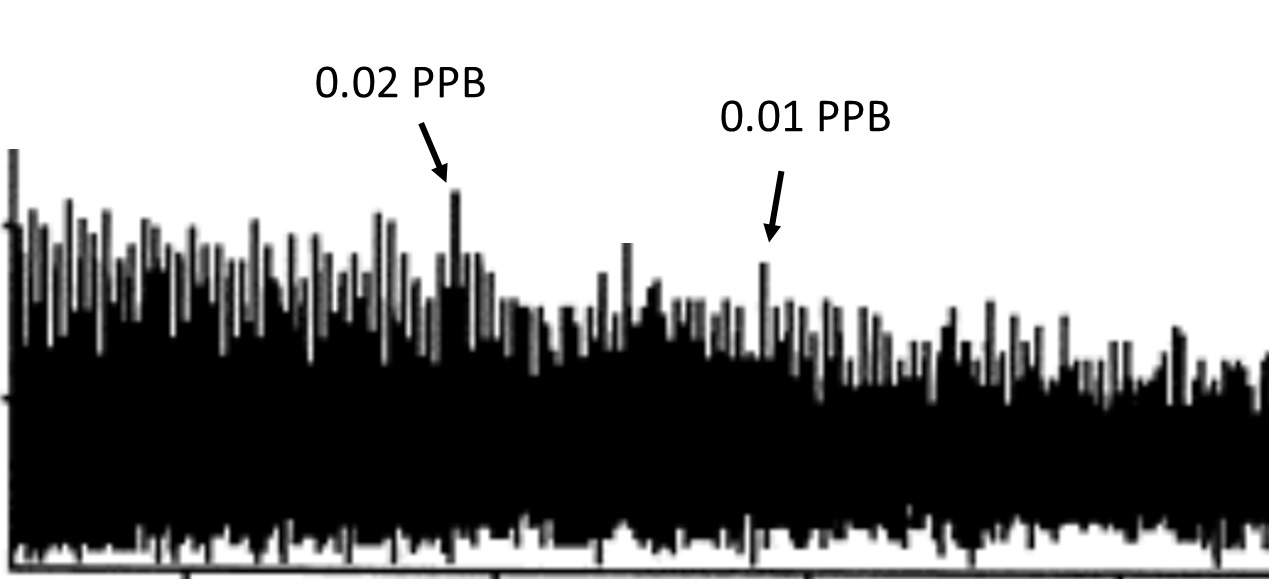

What does this have to do with your PSA? A level of 0.01 PPB is so small that it’s pretty close to instrument noise, and so is 0.02 PPB. These two signals can be hard to tell from noise:

So my PSA doubled, but the increase is still so small that it’s right at the limit of what the instrument can detect. I’ll repeat the important part: it’s right at the limit of what the instrument can detect. This is a bad signal-to-noise ratio because the signal is insignificant.

Dude: You don’t have cancer again.

(For a more technical discussion of noise, check out UMD Professor Tom O'Haver’s excellent tutorial on signal processing.)

Instrument noise isn’t the only thing that can complicate our understanding of PSA results. Lab procedures are important, too.

4. How they actually analyze your blood sample

If you search online for this, all you’ll get is “they take your blood and send it to a lab.” Yes, thank you, I know that. I have the hole in my arm. I needed to know the actual laboratory procedure so I could get an idea of all the things that could go wrong to screw with the PSA results. Because your results are only as good as your instruments, right?

The actual thing they do with your blood is called electrochemiluminescence. “Electro” means there’s electricity; “chemi” means there’s a chemical reaction, and “luminescence” means something emits light. From this point forward we’ll call it electro-whatever. If you want a deep dive into the hardcore science you can go here and scroll down to section 6.1.3. Or you can read this. Here is the extremely simple version of how it works:

Your blood sample is put into a liquid that contains microscopic particles of platinum and some chemicals

An electric current is run through the liquid

A chemical reaction takes place

The PSA causes something in the liquid to glow.

You would not be able to see any of this happening with your eyes—the glow has to be measured by an instrument. What is important is that electro-whatever is a complex process, and the more complex something is, the more likely something can get screwed up. Here’s a partial list of what can go wrong:

Does the liquid have the right ingredients?

Was the liquid measured out correctly?

Is the right amount of platinum in there?

Is the platinum contaminated?

Did they run the right amount current through it?

Any of those will alter the results of your PSA, but honestly, the chance of them happening is pretty small. Here’s two more:

Are there electrical or magnetic devices nearby that could interfere with the very delicate instrument?

Were you dehydrated when you got your blood drawn?

The electrical interference is generally well controlled. But what if there was a surge in the outlet the instrument is plugged into? Hopefully the lab tech remembers to stash their phone. And your blood itself? Well, that’s a pretty big variable.

(And here’s one more: Solar flares. No joke, it’s 2025 and right now the Sun is very active spewing out solar flares, many of which hit the Earth. The Sun does this every 11 years, this time starting in 2024. Remember those awesome northern lights in summer 2024? They sure were pretty! But Sun activity can mess with sensitive lab equipment.)

Electro-whatever is widely used because quality control is easier than other procedures. It’s also fast, it has a low signal-to-noise ratio, and it’s very, very, very precise. And precision is the problem. Precision is keeping you up at night.

In our society, we are conditioned to want a lot of data, the best data, and the most precise data. We don’t buy stuff without data. We don’t try restaurants without data. We don’t go pee without data. We’re told to make data-driven decisions.4 Business managers want data. Education administrators want data. Political campaigns want data. Because data = good. Get the best. Get the most. Gobble it up.

Electro-whatever can tell the difference between 0.015 nanograms and 0.021 nanograms of PSA. It can spot a difference of six one-thousandths of a billionth of a gram.

And I had to stop and think: Do I really need to know about a PSA fluctuation of 0.000000000006 grams? Does knowing that somehow make my life better? Is 0.000000000006 the difference between not having cancer and having cancer?

No, no, and NO.

Look, if the cancer is really back, your PSA will go way higher than 0.021 ppb, and it won’t just stay there, it will keep going higher. Like 0.1 —> 0.2 —> 0.4 and on up. If your PSA is wobbling around zero-point-zero-something then you should not worry about that.

So unclench, my dudes: We don’t have cancer again. Not today.

My thanks to Daniel Flora, MD, PharmD for pointing me to electrochemiluminescence. Special thanks to Mr. Mark Stevenson—may your PSAs forever wobble around zero-point-zero-something, mate. Cheers!

Mass, yes, I know. Let it go for now.

If you live in a small town, this will inevitably happen. Rural healthcare in the US is a real problem.

Mobile phones emit surprisingly strong electric and magnetic fields. Wave one over a compass sometime.

I’m so bloody sick of that phrase. Usually the people telling you to do that have no idea what to actually do with data.

Anthony, thanks for this incredibly detailed analysis. I've noticed that prostate cancer tends to make men with a wide variety of backgrounds experts in explaining detailed medical concepts. That's what happens when you feel like "your life depends" on knowing this stuff.

Great explanations, Anthony! You've got a great knack for explaining things.

With everything going on, we forget how tiring all this uncertainty can be. I hope you're having a good weekend.